There comes a point in every flute performance major’s

education where the plague of orchestral excerpts begins; yet with so many

orchestral works, how does a student decide which excerpts need to be mastered

sooner rather than later? Based off a

collection of audition set lists collected between May 2007 and February 2012,

a total of 11, six works stand out among

the rest: a Mozart concerto (usually G Major), Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, Brahms’ Symphony

No.4, Debussy’s Prelude to Afternoon

of a Faun, Mendelssohn’s Midsummer

Night’s Dream, and Stravinsky’s Firebird

Suite.[1] Why do these excerpts consistently appear on

lists? What is the audition committee

listening for? How do you prepare these

excerpts for a professional audition?

Knowing the answers to these questions give a flutist the foundation of

how to prepare any excerpt for a professional audition because, in reality,

excerpts aren't so different with regard to why they appear on a professional

orchestral audition list.

There are certain aspects of playing that are assumed in a

professional audition setting. The

committee is not listening for correct notes because if you are auditioning at

a professional level you should already know all the notes. What the audition committee is really looking

for in your playing are the nuts and bolts: internal pulse and rhythmic

precision, and good tone and pitch quality.

These qualities must be present in your playing. However, while demonstrating your mastery in

the foundation of musical performance you must simultaneously “move” the

committee with your musicianship. This

includes “expressivity, musicality, … phrasing flexibility, and an overall

sense of musical context.”[2] In order to fully understand the musical

context of the excerpt you are playing you should study a complete full score

of the pieces so that you know the inner working of the interacting musical

lines; you need to know how you fit into the big picture. It is also important to listen to multiple

reputable recordings to get the general sense of tempo and how the entire piece

sounds. “Members of audition committees

are used to hearing the music performed in context. They will sense a candidate’s familiarity—or

unfamiliarity—with style, tempo, and orchestration.”[3] In particular, the style with which you play

can be very telling of your knowledge of the historical context of the excerpt;

for example, the treatment of ornaments, such as trills, has been different

throughout the musical eras.

The first excerpt you will play at a professional audition

is a concerto; in most cases, the exposition to Mozart’s Concerto in G Major serves as your introduction to the

committee. Some orchestras will ask for you

to play with an accompanist, which they provide, while others will have you

play by yourself. If you play with an

accompanist make sure that you tune carefully to the piano; playing an

accompanied solo gives the committee “a sense of the candidate’s ability to adjust

to a prevailing level of pitch.”[4] In other words, they want to know how well

you play with someone else: do you feel the same pulse and are you listening

for intonation. The Mozart concerto is

the first opportunity you get to demonstrate all of your nuts and bolts, such

as rhythmic accuracy, and, more importantly, your musicianship. Mozart’s Concerto

in G Major is a piece that flutists will constantly work on throughout

their career and often they will work on it with multiple teachers, all with

different opinions on how to play Mozart.

The interpretation of the music is the icing on the cake; the musical

lines are challenging in their own rite.

The interval jumps and demanding sixteenth passages make a very dense

cake batter waiting to be cooked. On top

of that, at an audition you must prove to the committee that the way you play

the concerto is how Mozart intended it to be played. Because the parts do not include much

indication on dynamics, style, or articulation, as good musicians of Mozart’s time

would simply know how to play, it is your job to figure it out. This is one example of when recordings are

indispensable.

The first excerpt you will play at a professional audition

is a concerto; in most cases, the exposition to Mozart’s Concerto in G Major serves as your introduction to the

committee. Some orchestras will ask for you

to play with an accompanist, which they provide, while others will have you

play by yourself. If you play with an

accompanist make sure that you tune carefully to the piano; playing an

accompanied solo gives the committee “a sense of the candidate’s ability to adjust

to a prevailing level of pitch.”[4] In other words, they want to know how well

you play with someone else: do you feel the same pulse and are you listening

for intonation. The Mozart concerto is

the first opportunity you get to demonstrate all of your nuts and bolts, such

as rhythmic accuracy, and, more importantly, your musicianship. Mozart’s Concerto

in G Major is a piece that flutists will constantly work on throughout

their career and often they will work on it with multiple teachers, all with

different opinions on how to play Mozart.

The interpretation of the music is the icing on the cake; the musical

lines are challenging in their own rite.

The interval jumps and demanding sixteenth passages make a very dense

cake batter waiting to be cooked. On top

of that, at an audition you must prove to the committee that the way you play

the concerto is how Mozart intended it to be played. Because the parts do not include much

indication on dynamics, style, or articulation, as good musicians of Mozart’s time

would simply know how to play, it is your job to figure it out. This is one example of when recordings are

indispensable.

Beethoven’s Leonore

Overture No. 3 is the excerpt that defines the nuts and bolts of

playing. You will often find measures 1-36

and 278-360 on any given audition list, be it a principal, second flute, or

piccolo audition. The opening of the

piece may not seem challenging, but the dynamics and intimate atmosphere of the

“Adagio” mean that tonal control is the name of the game. From measures 20-36, but in particular

measures 20-24, you have to be consistent with your articulations; the

sixteenth note triplets should be short while the eighth notes should be legato

– this four measure passage must also maintain a soft dynamic and be constantly

moving forward despite the rests and staccato markings. It is also important that the vibrato used

fits into the character of the delicate tone of the opening of the

overture. The solo beginning in measure

328 calls for energy, but the excitement of the musical line is lost if the

pulse and pitch are unstable, the rhythm is not accurate, the articulations are

not clear, and the tonal intensity is not sustained. The D at the end of the solo, while at a soft

dynamic, must maintain all the previous intensity of the solo and the pitch

must be consistent; the soloist cannot let up in any way. Finally, after all the technical preparation

it is important to be musical and expressive throughout.

The solo excerpt from Brahms’ Symphony No. 4 appears short and extremely basic; however, it is

requested so much that there must be something more to it than it seems. The first thing you may notice is that the

solo begins on a high E and ends on a low E.

In the span of two octaves, Brahms explores the beautiful colors created

in the varying registers of the flute.

You have to pull the listener, creating a constant building tension,

through the twelve measure solo. Each

note needs to melt in to each successive pitch – the solo should be smooth in

its expression. The goal of the one long

phrase is to reach E major at its conclusion although it climaxes in measure

101 on the high F#. If you do not push

the phrase forward, the solo will not only be boring for you to play, it will

be extremely boring to listen to. There

is a wide range of dynamics to play with and you have to use them to make

smaller phrases that will support the overall structure, the journey from high

E to low E.

Every flute player knows two key things about C#: it is an

awful note on the flute and it is the first note heard in Debussy’s Prèlude à l’après-midi d’un fauna. Therefore the primary concern of this excerpt

is to find a stable and consistent, in pitch, C#. Your familiarity with the context in which

you are playing is also essential in this excerpt as you play the same solo

multiple times in different settings; the first solo is flute alone, but the

sequential solos are accompanied by different groups of instruments which means

that you should play them differently in order to create different atmospheres

with the same musical content. This

excerpt gives you the opportunity to explore tone colors. The other challenge of this excerpt is to

keep the long phrases interesting and moving with out exaggerating dynamic, as

the solo is often marked at piano, or

speeding up the pulse. Air support is

key in this excerpt and you may have to practice the solo with a metronome set

faster than the tempo marked so that you can get the solo in one breathe. If you practice with a metronome and slowly pull

the tempo back to the marked tempo you will build your breathing endurance. However, you should not sacrifice the musical

line and your expressivity to get the solo in one breath; it is better to take

a musical breath—meaning that you put the breath and execute the breath in a

way that makes sense and adds to the musical line—than let your lack of breath

take away from your ability to play the line comfortably.

Every flute player knows two key things about C#: it is an

awful note on the flute and it is the first note heard in Debussy’s Prèlude à l’après-midi d’un fauna. Therefore the primary concern of this excerpt

is to find a stable and consistent, in pitch, C#. Your familiarity with the context in which

you are playing is also essential in this excerpt as you play the same solo

multiple times in different settings; the first solo is flute alone, but the

sequential solos are accompanied by different groups of instruments which means

that you should play them differently in order to create different atmospheres

with the same musical content. This

excerpt gives you the opportunity to explore tone colors. The other challenge of this excerpt is to

keep the long phrases interesting and moving with out exaggerating dynamic, as

the solo is often marked at piano, or

speeding up the pulse. Air support is

key in this excerpt and you may have to practice the solo with a metronome set

faster than the tempo marked so that you can get the solo in one breathe. If you practice with a metronome and slowly pull

the tempo back to the marked tempo you will build your breathing endurance. However, you should not sacrifice the musical

line and your expressivity to get the solo in one breath; it is better to take

a musical breath—meaning that you put the breath and execute the breath in a

way that makes sense and adds to the musical line—than let your lack of breath

take away from your ability to play the line comfortably.

If there were ever an excerpt to plague the audition lists

for flute positions, it would be the “Scherzo” of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. From a technical standpoint, rhythmic

accuracy and light but clear articulation will get the job done. With only two opportunities for a quick

breath and the general lack of dynamic suggestion by the composer keeping up

with the rest of the orchestra is a task.

You cannot slow down and you cannot take too long of a breath. Luckily, the solo, for the most part, is

written in a soft dynamic; yet you still have to project over the orchestra. Most flutists use double tonguing on this

excerpt and it is good idea to practice this excerpt a click slower and a click

faster than the traditionally practiced tempo.

At an audition, the committee may ask you to play the excerpt faster and

clarinetist will generally be appreciative if you do not play the solo as fast

as you can double tongue due to their lack of double tongue. In order to achieve flawless execution of

this excerpt, practice at a slow tempo with a metronome and at the slow tempo

begin to train yourself to take quick, efficient filling breathes. As the tempo gets faster you will have less

time to take in air. Remember to be

relaxed when you breathe as tension in your throat hinders your ability to

breathe.

Without doubt, the “Variation de L’oiseau de feu” excerpt

from Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite is

the most difficult from a technical view.

Above all else, pulse and rhythmic accuracy are the foundation to your

success in playing this excerpt.

Practicing this in a slow six with a metronome will help you feel more

secure when you eventually play it in a faster two. It is also important to extremely observant

of the various articulations Stravinsky uses in the piece. To achieve all the dynamics, pitches,

rhythms, and articulations at the tempo marked, slow practice should be your

mantra. Again, the context of the

excerpt is important as the flute line is directly related to the piccolo line;

the two lines intersect and create an overlapping musical conversation.

For a young flutist who has never taken a professional

audition before, the preparation and idea of taking an audition may be

overwhelming. But it is important to

keep a couple things in mind; for one, although technical perfection is expected,

one or two technical mistakes won’t end your career if you demonstrate

knowledge of the piece through your phrasing and expressivity. Despite the fact that most musicians take an

obscene number of auditions before winning a position, flutists with little to

no experience have also won positions in their first few auditions. Keep an open mind and prepare yourself

thoroughly for an audition by listening to recordings, studying scores, being

aware of where the excerpt fits in to the overall context, practice with a

metronome and tuner religiously. In an

audition you have very little time to “move” the committee and communicate to

them that regardless of what they have heard before you know what you are

doing and you are the person who should sit in the chair that they are

offering.

Sources:

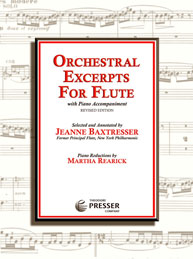

Baxtresser, Jeanne. Orchestral Excerpts for Flute. Presser

Company (2008)

Nelson, Florence . “Parloff Q&A”, Pipline. Fall 2011. Pages 5-7.

[1] Out of

the 11 lists Mozart appeared 10 times (one list requested a concerto of the

applicant’s choosing), Beethoven appeared 10 times, Brahms 8 times, Debussy 9

times, Mendelssohn 11 times, and Stravinsky 7 times.

[2] Florence Nelson. “Parloff Q&A”, Pipline. Fall 2011. Page 5.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.,

page 7.

No comments:

Post a Comment